Prices of other Commodities:

There are three types of commodities in this

context.

Substitutes:

If a rise (or fall) in the price of one

commodity leads to an increase (or decline) in the demand for another

commodity, the two commodities are said to be substitutes. In other words,

substitutes are those commodities that satisfy similar wants, such as tea and

coffee.

If the price of coffee falls, the demand for

coffee rises which brings a fall in the demand for tea because the consumers of

tea shift their demand to coffee which has become cheaper. On the other hand,

if the price of coffee rises, its demand will fall. But the demand for tea will

rise because the consumers of coffee will shift their demand to tea.

Complementary Commodities:

Where the demand for two commodities is linked

to each other, such as cars and petrol, bread and butter, tea and sugar, etc.,

they are said to be complementary goods. Complementary goods are those which

cannot be used without each other. If, say, the price of cars rises and they

become expensive, the demand for them will fall and so will the demand for

petrol. On the contrary, if the price of cars falls and they become cheaper,

the demand for them will increase and so will the demand for petrol.

Unrelated Goods:

If the two commodities are unrelated, say

refrigerator and bicycle, a change in the price of one will have no effect on

the quantity demanded of the other.

3. Income:

A rise in the consumer’s

income raises the demand for a commodity, and a fall in his income reduces the

demand for it.

4.

Tastes:

When there is a change in the

tastes of consumers in favor of a commodity, say due to fashion, its demand

will rise, with no change in its price, in the prices of other commodities, and

in the income of the consumer. On the other hand, a change in tastes against a

commodity leads to a fall in its demand, while other factors affecting demand

remain unchanged.

An Individuals Demand Schedule

and Curve:

An individual consumer’s

demand refers to the quantities of a commodity demanded by him at various

prices, other things remaining equal (y, pr, and t). An individual’s demand for

commodity “is shown on the demand schedule and on the demand curve. A demand

schedule is a list of prices and quantities and its graphic representation is a

demand curve.

Table 10.1: Demand Schedule:

|

Price (Rs.) |

Quantity (units) |

|

6 |

10 |

|

5 |

20 |

|

4 |

30 |

|

3 |

40 |

|

2 |

60 |

|

1 |

80 |

The

demand schedule reveals that when the price is Rs. 6, the quantity demanded is

10 units. If the price happens to be Rs 5, the quantity demanded is 20 units,

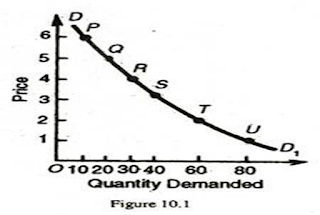

and so on. In Figure 10.1, DD1 is the

demand curve drawn on the basis of the above demand schedule. The dotted points

D, P, Q, R, S, T, and U show the various price-quantity combinations.

Marshall

calls them “demand points”. The first combination is represented by the first

dot and the remaining price- quantity combinations move to the right toward D1.

The Market Demand Schedule and

Curve:

In a market, there is not one

consumer but many consumers of a commodity. The market demand of a commodity is

depicted on a demanding schedule and a demand curve. They show the sum total of

various quantities demanded by all the individuals at various prices.

Suppose there are three

individuals A, В, and С in a market who purchase the commodity. The demand

schedule for the commodity is depicted in Table 10.2.

The last column (5) of the

Table represents the market demand for the commodity at various prices. It is

arrived at by adding columns (2), (3), and (4) representing the demand of

consumers A, В, and С respectively. The relation between columns (1) and (5)

shows the market demand schedule. When the price is very high Rs. 6 per kg. the

market demand for the commodity is 70 kgs. As the price falls, the demand

increases. When the price is the lowest Re. 1 per kg., the market demand per

week is 360 kgs.

TABLE 10.2: MARKET DEMAND SCHEDULE:

|

Price per kg. (Rs.) (1) |

A (2) |

Quantity Demanded in kgs. В +

(3) + |

С (4) |

Total Demand (5) |

|

6 |

10 |

20 |

40 |

70 |

|

5 |

20 |

40 |

60 |

120 |

|

4 |

30 |

60 |

80 |

170 |

|

3 |

40 |

80 |

100 |

220 |

|

2 |

60 |

100 |

120 |

280 |

|

1 |

80 |

120 |

160 |

360 |

From

Table 10.2 we draw the market demand curve in Figure 10.2. DM is the market demand curve which is the

horizontal summation of all the individual demand curves DA + DB + DC. The market demand for a commodity depends on all

factors that determine an individual’s demand.

But a better way of drawing a

market demand curve is to add together sideways (lateral summation) of all the

individual demand curves. In this case, the different quantities demanded by

consumers at one price are represented on each individual demand curve and then

a lateral summation is done, as shown in Figure 10.3.

Suppose

there are three individuals A, В, and С in a market who buy OA, OB, and ОС

quantities of the commodity at the price OP, as shown in Panels (A), (В), and

(C) respectively in Figurel0.3. In the market, OQ quantity will be bought which

is made up by adding together the quantities OA, OB, and ОС. The market demand

curve, DM is obtained by the lateral summation of the

individual demand curves DA, DB, and Dcin panel (D).

Changes in Demand:

An

individual’s demand curve is drawn on the assumption that factors such as

prices of other commodities, income, and tastes influencing his demand remain

constant. What happens to an individual’s demand curve if there is a change in

any one of the factors affecting his demand, the other factors remaining

constant? When any one of the factors changes, the entire demand curve shifts.

When an individual’s money income rises, other factors remain constant, and his

demand curve for a commodity will shift upwards to the right. He will buy more

of the commodity at a given price, as shown in Figure 10.4. Before the rise in

his income, the consumer is buying OQ1 quantity at

OP price on the D1D1 demand

curve.

With

the increase in income, his demand curve D1D1 shifts to the right as D2D2. He now buys

more quantity OQ2 at the same price as OP. When

the consumer buys more of the commodity at a given price, this is called the

increase in demand. On the contrary, if his income falls, his demand curve will

shift to the left. He will buy less of the commodity at the same price, as

shown in Figure 10.5. Before the fall in his income, the consumer is on the

demand curve D1D1where he is

buying OQ1 of the commodity at OP Price. He now buys less

quantity OP price at the given price OP. When the consumer buys less of the

commodity at a given price, this is called a decrease in demand.

Demand curves are thus not

stationary. Rather, they shift to the right or left due to a number of causes.

There are changes in tastes, habits, and customs of the consumers; changes in

income expenditure; changes in the prices of substitutes and complements;

expectations about future changes in prices and incomes and changes in the age

and composition of the population, etc.

A

movement along a demand curve takes place when there is a change in the

quantity demanded due to a change in the commodity’s own price. This is

illustrated in Figure 10.6 which shows that when the price is OP1 the quantity demanded is OQ1 with the fall in price, there has been a

downward movement along the same demand curve D1D1from point A to B. This is known as an extension in

demand. On the contrary, if we take В as the original price-demand point, then

a rise in the price from OP2 to OP1 leads to a fall in the quantity demanded from

OQ2 to OQ1. The consumer

moves upwards along the same demand curve D1D1 from point В to A. This is known as the contraction in demand.

The Law of Demand:

The law of demand expresses a

relationship between the quantity demanded and its price. It may be defined in

Marshall’s words as “the amount demanded increases with a fall in price, and

diminishes with a rise in price.” Thus it expresses an inverse relation between

price and demand.

The law refers to the

direction in which quantity demanded changes with a change in price. In the

figure, it is represented by the slope of the demand curve which is normally

negative throughout its length. The inverse price-demand relationship is based

on other things remaining equal. This phrase points toward certain important

assumptions on which this law is based.

It’s Assumptions. These

assumptions are:

(i)

there is no change in the tastes and preferences of the

consumer;

(ii)

the income of the consumer remains constant;

(iii)

there is no change in customs;

(iv)

the commodity to be used should not confer distinction on the

consumer;

(v)

there should not be any substitutes for the commodity;

(vi)

there should not be any change in the prices of other products;

(vii) there should not be any possibility of change

in the price of the product being used;

(viii) there should not be any

change in the quality of the product; and

(ix)

the habits of the consumers should remain unchanged. Given these

conditions, the law of demand operates. If there is change even in one of these

conditions, it will stop operating.

Explain the law with the help

of Table 10.1 and Figure 10.1.

Causes

of Downward Sloping Demand Curve:

Why does a demand curve slope

downward from left to right? The reasons for this also clarify the working of

the law of demand. The following are the main reasons for the downward sloping

demand curve.

(1) The law of demand is

based on the law of Diminishing Marginal Utility. According to this law, when a

consumer buys more units of a commodity, the marginal utility of that commodity

continues to decline. Therefore, the consumer will buy more units of that

commodity only when its price falls. When fewer units are available, the utility

will be high and the consumer will be prepared to pay more for the commodity.

This proves that the demand will be more at a lower price and it will be less

at a higher price. That is why the demand curve is downward sloping.

(2) Every commodity has

certain consumers but when its price falls, new consumers start consuming it,

as a result, demand increases. On the contrary, with the increase in the price

of the product, many consumers will either reduce or stop their consumption and

the demand will be reduced. Thus, due to the price effect when consumers

consume more or less of the commodity, the demand curve slopes downward.

(3) When the price of a

commodity falls, the real income of the consumer increases because he has to

spend less in order to buy the same quantity. On the contrary, with the rise in

the price of the commodity, the real income of the consumer falls. This is

called the income effect. Under the influence of this effect, with the fall in

the price of the commodity, the consumer buys more of it and also spends a

portion of the increased income on buying other commodities. For instance, with

the fall in the price of milk, he will buy more of it but at the same time, he

will increase the demand for other commodities. On the other hand, with the

increase in the price of milk, he will reduce its demand. The income effect of a

change in the price of an ordinary commodity is positive, and the demand curve

slopes downward.

(4) The other effect of

change in the price of the commodity is the substitution effect. With the fall

in the price of a commodity, the prices of its substitutes remain the same, and consumers will buy more of this commodity rather than the substitutes. As a

result, its demand will increase. On the contrary, with the rise in the price

of the commodity (under consideration) its demand will fall, given the prices

of the substitutes. For instance, with the fall in the price of tea, the price

of coffee being unchanged, the demand for tea will rise, and contrariwise, with

the increase in the price of tea, its demand will fall.

(5) There are persons in

different income groups in every society but the majority is in the low-income

group. The downward sloping demand curve depends upon this group. Ordinary

people buy more when the price falls and less when the price rises. The rich do not

have any effect on the demand curve because they are capable of buying the same

quantity even at a higher price.

(6) There are different uses

of certain commodities and services that are responsible for the negative slope

of the demand curve. With the increase in the price of such products, they will

be used only for more important uses and their demand will fall. On the

contrary, with the fall in price, they will be put to various uses and their

demand will rise. For instance, with the increase in the electricity charges,

power will be used primarily for domestic lighting, but if the charges are

reduced, people will use power for cooking, fans, heaters, etc.

Exceptions

to the Law of Demand:

In certain cases, the demand

curve slopes up from left to right, i.e., it has a positive slope. Under

certain circumstances, consumers buy more when the price of a commodity rises,

and less when the price falls, as shown by the D curve in Figure 10.7. Many causes

are attributed to an upward-sloping demand curve.

(i) War:

If a shortage is feared in

anticipation of war, people “may start buying for building stocks or for

hoarding even when the” price rises.

(ii) Depression:

During a depression, the

prices of commodities are very low and the demand for them is also less. This

is because of the lack of purchasing power among consumers.

(iii) Giffen Paradox:

If a commodity happens to be

a necessity of life like wheat and its price goes up, consumers are forced to

curtail the consumption of more expensive foods like meat and fish, and wheat

being still the cheapest, the food they will consume more of it. The Marshallian

example is applicable to developed economies. In the case of an underdeveloped

economy, with the fall in the price of an inferior commodity like maize,

consumers will start consuming more of the superior commodity like wheat. As a

result, the demand for maize will fall. This is what Marshall called the Giffen

Paradox which makes the demand curve have a positive slope.

(iv) Demonstration Effect:

If consumers are affected by

the principle of conspicuous consumption or demonstration effect, they will

like to buy more of those commodities which confer distinction on the

possessor, when their prices rise. On the other hand, with the fall in the

prices of such articles, their demand falls, as is the case with diamonds.

(v) Ignorance Effect:

Consumers buy more at a

higher price under the influence of the “ignorance effect”, where a commodity

may be mistaken for some other commodity, due to deceptive packing, label, etc.

(vi) Speculation:

Marshall mentions speculation

as one of the important exceptions to the downward sloping demand curve.

According to him, the law of demand does not apply to the demand in a campaign

between groups of speculators. When a group unloads a great quantity of a thing

onto the market, the price falls and the other group begins buying it. When it

has raised the price of the thing, it arranges to sell a great deal quietly.

Thus when the price rises, demand also increases.

Income Demand:

We have so far studied price

demand in its various aspects, keeping other things constant. Let us now study

income demand which indicates the relationship between income and the quantity

of a commodity demanded. It relates to the various quantities of a commodity or

service that will be bought by the consumer at various levels of income in a

given period of time, other things being equal. Things that are assumed to

remain equal are the price of the commodity in question, the prices of related

commodities, and the tastes, preferences, and habits of the consumer for it. The

income-demand function for a commodity is written as D – f (y). The

income-demand relationship is usually direct.

The

demand for the commodity increases with the rise in income and decreases with

the fall in income, as shown in Figure 10.8 (A). When income is OI, the quantity

demanded is OQ, and when income rises to OI1 the

quantity demanded also increases to OQ1. The reverse

case can also be shown likewise. Thus, the income demand curve ID has a

positive slope. But this slope is in the case of normal goods.

Let

us take the case of a consumer who is in the habit of consuming an inferior

good. So long as his income remains below a particular level of his minimum

subsistence, he will continue to buy more of this inferior good even when his

income increases by small increments. But when his income starts rising above

that level, he reduces his demand for the inferior good. In Figure 10.8 (B), 01

is the minimum subsistence level of income where he buys the IQ of the commodity.

At this level, this commodity is a normal good for him so he increases

its consumption when his income rises gradually from Ol1 to OI2 and to OI.

As “his income rises above 01, he starts buying less of the commodity. For

instance, at QI3 income level, he buys I3Q3which is less

than his IQ. Thus, in the case of inferior goods, the income demand curve ID is

backward sloping.

Cross Demand:

Let us now take the case of

related goods and how the change in the price of one affects the demand for the

other. This is known as cross demand and is written as D = f (pr).

Related goods are of two

types, substitutes and complementary. In the case of substitute or competitive

goods, a rise in the price of one good A raises the demand for the other good

B, “the price of В remaining the same.

The

opposite holds in the case of a fall in the price of A when the demand for В

falls. Figure 10.9 (A) illustrates it. When the price of good A increases from

OA to CM, the quantity of good В “also increases from OB to OB1. The cross-demand curve CD for substitutes is

positively sloping. For with the rise in the price of A, the consumers will

shift their demand to В since the price of В remains unchanged. It is also

assumed here that the incomes, tastes, preferences, etc. of the consumers do

not change.

In

case the two goods are complementary or jointly demanded, a rise in the price

of one good A will bring a fall in the demand for good B. Conversely, a fall in

the price of A will raise the demand for B. This is illustrated in Figure 10.9

(B) where when the price of A falls from OA, to OA, the demand for В increases

from OB to OB1. The demand curve in the case

of complementary goods is negatively sloping like the ordinary demand curve.

If, however, the two goods

are independent, a change in the price of A will have no effect on the demand for

B. We seldom study the relation between two unrelated goods like wheat and

chairs. Mostly as consumers, we are concerned with the price-demand relation of

substitutes and complementary goods.

Short-Run and Long-Run Demand

Curves:

The distinction may be made

between short-run and long-run demand curves. In the case of perishable

commodities such as vegetables, fruit, milk, etc., the change in quantity

demanded to a change in price occurs quickly. For such commodities, there is a

single demand curve with the usual negative slope.

But in the case of durable

commodities such as gadgets, machines, clothes, and others, a change in price

will not have its ultimate effect on the quantity demanded until the existing

stock of the commodity is adjusted which may take a long time. A short-run

demand curve shows the change in quantity demanded to a change in price, given

the existing stock of the durable commodity and the supplies of its

substitutes. On the other hand, the long-run demand curve shows the change in

quantity demanded to a change in price after all adjustments “have been made in

the long-run.

The

relation between the short-run and long-run demand curves is shown in Figure

10.10. Suppose initially consumers are fully adjusted to OP1 price and OQ1 quantity

demanded with equilibrium at point E1, on the

short-run demand curve D1. Now assume that the price falls to OP. In the short-run, consumers will react along the D1 curve and increase the quantity demanded to OQ1 with equilibrium at point E1 After the lapse of some time when adjustments

are made to the new price OP2, a new

equilibrium will be reached at point E3 with

quantity demanded at OQ1. There will be

now a new short-run demand curve passing through point E1 A further fall in the price to ОР1 would first lead to a short-run equilibrium at

point E4 with OQA quantity

demanded and ultimately to a new equilibrium at point E5 with OQ5 quantity

demanded on the short-run demand curve, D1 A line

passing through the final equilibrium points E1, E3 and E5 at each

price traces out the long-run demand curve DL. The long-run

demand curve Dl is flatter than the

short-run demand curves D1, D2, and D3.

Defects of Utility Analysis or

Demand Theory:

The Marshallian utility

analysis has many defects and weaknesses which are discussed below.

(1)

Utility cannot be measured cardinally:

The entire Marshallian

utility analysis is based on the hypothesis that utility is cardinally measured

in ‘utils’ or units and that utility can be added and subtracted. For instance,

when a consumer takes the first chapati, he gets a utility equivalent to 15

units; from the second and third chapati “10 and 5 units respectively and when

he consumes the fourth chapati marginal utility becomes zero. If it is supposed

that he has no desire after the fourth chapati, the utility from the fifth will

be negative 5 units if he takes this chapati. In this way, the total utility in

each case will be 15, 25, 30, and 30, while from the fifth chapati the total

utility will be 25 (30-5).

Besides, the utility analysis

is based on the assumption that the consumer is aware of his preferences and

is capable of comparing them. For example, if the utility of one apple is 10

units, of a banana 20 units, and of an orange 40 units, it means that the

consumer gives twice the preference to banana as against apple and four times

to orange. It shows that utility is transitive. Hicks opines that the basis of

the utility analysis, that it is measurable, is defective because the utility is a

subjective and psychological concept that cannot be measured cardinally. In

reality, it can be measured ordinally.

(2)

Single Commodity Model is Unrealistic:

The utility analysis is a

single commodity model in which the utility of one commodity is regarded as independent of the other. Marshall considered substitutes and complementaries

as one commodity, but it makes the utility analysis unrealistic. For instance,

tea and coffee are substitute products. When there is a change in the stock of

any one product, there is a change in the marginal utility of both the products.

Suppose there is an increase in the stock of tea. There will not only be a fall in

the marginal utility of tea but also of coffee.

Similarly, a change in the

stock of coffee will bring a change in the marginal utility of both coffee and

tea. The effect of one commodity on the other, and vice versa is called the

cross effect. The utility analysis neglects the cross effects of substitutes,

complementaries, and unrelated goods. This makes the utility analysis

unrealistic. To overcome it, Hicks constructed the two-commodity model in the

indifference curve approach.

(3)

Money is an Imperfect Measure of Utility:

Marshall measured utility in

terms of money, but money is an incorrect and imperfect measure of utility

because the value of money often changes. If there is a fall in the value of

money, the consumer will not be getting the same utility from the homogeneous

units of a commodity at different times. A fall in the value of money is a

natural consequence of rising prices.

Again, if two consumers spend

the same amount of money at a time, they will not be getting equal utilities

because the amount of utility depends upon the intensity of desire of each

consumer for the commodity. For instance, consumer A may be getting more

utility than В by spending the same amount of money, if his “intensity of

desire for the commodity is greater. Thus, money is an imperfect and unreliable

measuring rod of utility.

(4)

Marginal Utility of Money is not constant:

The utility analysis assumes

the marginal utility of money to be constant. Marshall supported this argument

on the plea that a consumer spends only a small portion of his income on a

commodity at a time so that there is an insignificant reduction in the stock of

the remaining amount of money. But the fact is that a consumer does not buy

only one commodity but a number of commodities at a time. In this way, when a

major part of his income is spent on buying commodities, the marginal utility

of the remaining stock of money increases.

For instance, every consumer

spends a major portion of his income in the first week of the month to meet his

domestic requirements. After this, he spends the remaining amount of money

wisely. It implies that the utility of the remaining sum of money has

increased. Thus the assumption that the marginal utility of money remains

constant is away from reality and makes this analysis hypothetical.

(5)

Man is not Rational:

The utility analysis is based

on the assumption that the consumer is rational who prudently buys the

commodity and has the capacity to calculate the dis-utilities and utilities of

different commodities, and buys only those units which give him greater

utility. This assumption is also unrealistic because no consumer compares the

utility and disutility of each unit of a commodity while buying it. Rather,

he buys them under the influence of his desires, tastes, or habits. Moreover, the consumer’s income and prices of commodities also influence his purchases. Thus

the consumer does not buy commodities rationally. This makes the utility

analysis unrealistic and impracticable.

(6)

Utility Analysis does not study the Income Effect, Substitution Effect, and Price

Effect:

The greatest defect in the

utility analysis is that it ignores the study of income effect, substitution

effect, and price effect. The utility analysis does not explain the effect of a

rise or fall in the income of the consumer on the demand for the commodities.

It thus neglects the income effect. Again, when the change in the price of

one commodity there is a relative change the price of the other commodity,

the consumer substitute’s one for the other.

This is the substitution

effect that the utility analysis fails to discuss, being based on one- commodity model. Besides, when the price of one commodity changes, there is a

change in its demand and in the demand for related goods. This is the price

effect which is also ignored by the utility analysis. When say, the price of

good X falls the utility analysis only tells us that its demand will increase.

But it fails to analyze the income and substitution effects of a price fall via

the increase in the real income of the consumer.

(7)

Utility Analysis fails to clarify the Study of Inferior and Giffen Goods:

Marshall’s utility analysis

of demand does not clarify the fact as to why a fall in the prices of inferior

and Giffen goods leads to a decline in their demand. Marshall failed to explain

this paradox because the utility analysis does not discuss the income and

substitution effects of the price effect. This makes the Marshallian law of

demand incomplete.

(8)

The Assumption that the Consumer buys more Units of a Commodity when its Price

falls is Unrealistic:

The utility analysis of

demand is based on the assumption that the consumer buys more units of a

commodity when its price falls. It may be true in the case of food products

like oranges, bananas, apples, etc. but not in the case of durable goods. When,

for example, the price of a bicycle or radio falls, a consumer will not buy two

or three bicycles or radios. It is another thing that a rich man may buy two or

three cars, pairs of shoes and a variety of clothes, etc. But he does so

irrespectively of the fall in their prices because he is rich. The argument,

therefore, does not hold good in the case of an ordinary person.

(9)

This Analysis fails to explain the Demand for Indivisible Goods:

The utility analysis breaks

down in the case of durable consumer goods like scooters, transistors, radios,

etc. because they are indivisible. The consumer buys only one unit of such

commodities at a time so it is neither possible to calculate the marginal

utility of one unit nor can the demand schedule and the demand curve for that

good be drawn. Hence the utility analysis is not applicable to indivisible

goods.

These glaring defects in the

utility analysis led economists like Hicks to explain the demand analysis of

the consumer with the help of the indifference curve approach.

Exam studies telegram group

Exam studies

For daily current affairs

POWERPOINT PRESENTATION (PPT)

MCQ/Quiz/General Knowledge/Current Affairs/ H.P. GK.

Webinar-Workshop-FDP-Seminar 2022

Exam studies | |

For daily current affairs | |

POWERPOINT PRESENTATION (PPT) | |

MCQ/Quiz/General Knowledge/Current Affairs/ H.P. GK. | |

Webinar-Workshop-FDP-Seminar 2022 |

![Himachal Pradesh - General Knowledge (H.P.-GK) Important multiple choice questions [MCQ] Series-G [PDF]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEihP5ys_xY1amJSiIEX-cY2NLnL0-9UBNpv2MTUAeFLcs2pnfZKTYrt7Qd-n_r7M4evoPfvEdhHqdfZJOZSq9KYkrGcH_xqghVowGepqKTjk95dgtUVABcsuzhRcsWto5IrCi3jfZcRgnUztoalEsVLXewOeyf2k3keJIRTSQvEIfkRVVhFXlOSAxAK/w72-h72-p-k-no-nu/Untitled.png)

![Himachal Pradesh - General Knowledge (H.P.-GK) Important multiple choice questions [MCQ] Series-E [PDF]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgvoEofOEWgV2ZbKnHN0TIymi5Ri4OkMlEtZSBr-uBeGEIfoHH7VbEK_Znb2bog2mo5eWSYvhgC3VT2gUixmn_it7TP13EVdxDKI21dEHngzbUbjy0myZ6X86bS6IaqkkweK-uwRYQdW3GLNFQtUkWJhmffquskJFEii-4T0hAtUzte3rXwegACr8hy/w72-h72-p-k-no-nu/Series%20E.JPG.webp)

0 Comments